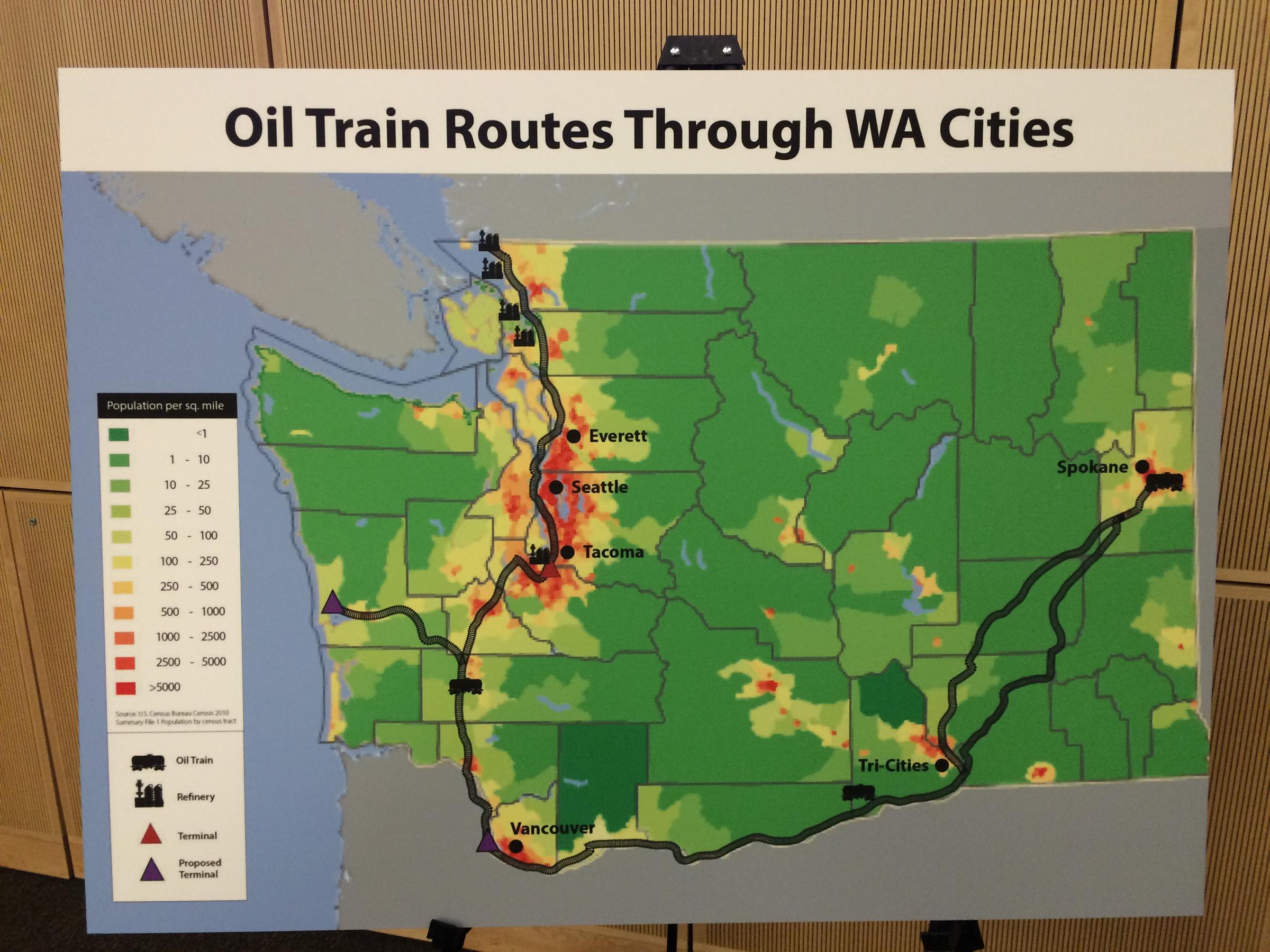

A map displayed by Senator Cantwell shows the route traveled by oil trains that enter Washington near Spokane.

Confronting the facts about a rickety industry.

Eric de Place and

Ben Stuckart on October 8, 2015

Sightline Institute

Sightline Editor’s note: The Seattle Times

recently published a guest opinion regarding oil trains. It contained

some unfortunate errors. Sightline Policy Director Eric de Place and

Spokane City Council President Ben Stuckart penned this response.

On September 13, the

Seattle Times published

an opinion piece

by Richard Berkowitz attacking, among other things, advocacy groups,

communities worried about oil trains, and research published by

Sightline Institute. Unfortunately, his article dismisses the threats

that oil trains pose to Northwest cities—and it fails to confront the

facts about a rickety, born-yesterday industry.

Here’s a fact: new projects could induce as many as

100 loaded crude oil trains per week

to transit Washington. That number, first published by Sightline

Institute, comes directly from adding up the industry’s own figures in

publicly available permitting documents.

Here’s another fact: no fewer than

10 oil trains have exploded in North America in the last two years, killing 47 people in one instance. That’s why some have taken to calling them “bomb trains.”

Newcomers to our rail system, these oil trains play no part in moving

the cargo that makes the Northwest economy tick. Far from boosting

commerce, oil trains threaten to derail it. Consider the case of Cold

Train, a Quincy, Washington company that, until recently, shipped

refrigerated fruits and vegetables.

The company went bust after its goods were crowded off the rails by coal and oil trains.

The owners of the now-defunct company are suing BNSF, but it’s already too late for the workers who lost their jobs.

“New projects could induce as many as 100 loaded crude oil trains per week to transit Washington.”

Terry Whiteside, who represents the Wheat and Barley Commissions for

many western states, says that “the huge increase in Bakken oil

movements and doubling of coal movements have contributed to

the worst service meltdown in two decades affecting all commodity movements in the northern tier.” A Cargill executive said much the same thing to the

Seattle Times in a 2014 story headlined, clearly enough,

“Oil trains crowd out grain shipments to NW ports.”

Coal and oil trains are a problem not only for farmers; they are also

a nightmare for on-street traffic congestion.

If new oil and coal terminal plans come to fruition, they could create

enough train traffic to shut down street crossings in eastern Washington

by an average of two to four hours every day. In Seattle, those delays

are likely to be shorter—perhaps averaging two hours a day—but they will

impact at least eight major streets, including arterials in Sodo

critical for freight movement.

Again, Sightline arrived at these figures simply by adding up what

the project backers themselves say in their permit applications and

factoring in estimated train speeds. Moreover, these vehicle delay

findings have been corroborated by two independent traffic consulting

firms,

Parametrix and

Gibson.

Yet worsening traffic is hardly oil trains’ worst insult: they can, and do, kill.

The first one seemed like a freak accident. An oil train derailed and

exploded in a Quebec village, incinerating 47 people. But then it kept

happening: train after train loaded with crude oil wobbled off the rails

and blew up, their towering infernos now well documented across the

internet.

Seattle, Spokane, and many other Northwest cities are directly in harm’s way. Seattle Assistant Fire Chief A.D. Vickery says,

“There’s no department in the world that could deal with a scenario like Quebec

or the most recent one in West Virginia. We simply don’t have the

economic resources to add additional firefighters, specialized

apparatus, and a number of things that would be required to deal with a

significant incident.” It’s a sentiment echoed by fire chiefs around the

region.

Berkowitz makes light of the risks of oil trains, but in truth they well illustrate

the stakes now facing the Northwest.

In just the last few years, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia

have seen serious proposals for two new oil pipelines, 10 new or

expanded coal export terminals, 14 oil-by-rail facilities, and at least

six new natural gas pipelines. If we permit them, these proposals will

reshape the economy of our state, from Spokane to Whatcom

County—clogging our rail lines, worsening our traffic congestion, and

physically endangering our communities. These are weighty decisions that

require careful scrutiny—not the plainly false and misleading rhetoric

that Berkowitz offers.