Northwest Tribes unite against giant coal, oil projects

As governments, tribal nations are uniquely empowered in some of the biggest environmental fights in Washington and willing to use that power.Seattle Times January 16, 2016 By Lynda V. Mapes

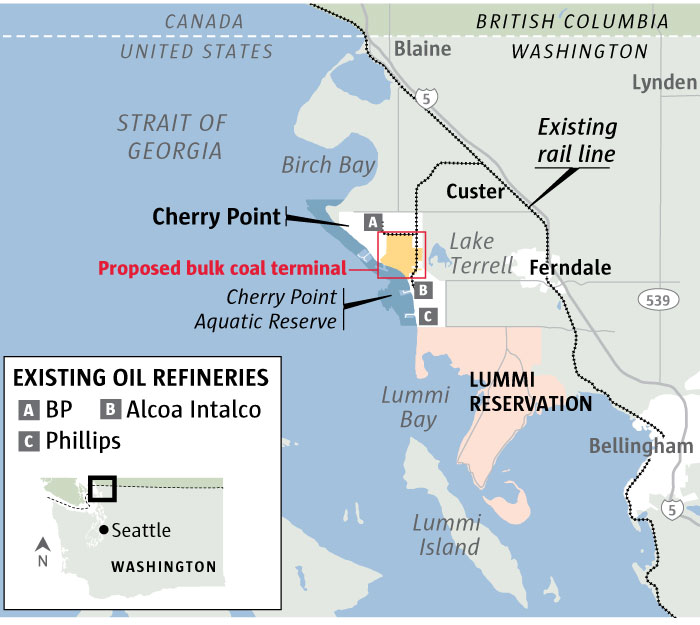

CHERRY POINT, Whatcom County — On this last bit of undeveloped coast between a smelter and two oil refineries, SSA Marine wants to build the biggest coal export terminal in North America, to load up some of the largest ships afloat arriving up to 487 times a year, mostly from Asian ports.

The blockbuster $665 million proposal is one of many fossil fuel transport projects under review in the region — from oil pipeline expansions in B.C., to oil-by-rail facilities in Southwest Washington and another coal port in Longview.

And while thousands of people have turned out to protest Washington turning into one of the largest fossil fuel hubs in the country, Northwest tribes appear best positioned to win the fight.

“This is different from an environmental group coming in and saying ‘you shouldn’t do this.’ Here, agencies’ discretion is limited,” said Robert Anderson, director of the Native American Law Center at the University of Washington School of Law. “Tribes have treaty rights and the U.S. has trust responsibility to uphold those rights. That is the game-changing possibility here.”

It’s a high-stakes power play. There’s already been blowback in Congress from Republican lawmakers and, if the tribes lose, that could create a bad precedent for them in future battles.

But tribes are standing together against the projects.

“Coal is black death,” said Brian Cladoosby, chairman at the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community near La Conner who, as president of the National Congress of American Indians, has brought a national voice to the opposition.

“There is no mitigation,” Cladoosby said. “We have to make a stand before this very destructive poison they want to introduce into our backyards. We say no.”

The Lummi Nation has demanded the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which is reviewing the so-called Gateway Pacific Terminal project, deny SSA’s permit application because it endangers the tribe’s treaty-protected fishing rights.

The Swinomish and Tulalip Tribes have sent similar letters to the Corps, and the Suquamish Tribe also is weighing in. “We have the same amount of commitment to treaty rights protection,” said Leonard Forsman chairman of the Suquamish tribe. “We are a team and we are working with them. We are very concerned about impacts on our fishery.”

The project is proposed in a state aquatic reserve and treaty protected fishing areas of five Washington Tribes. The uplands and waters are utilized by a menagerie of state and federally protected species, and what was once the best herring run in Puget Sound, already imperiled and targeted for recovery. The project also overlaps Xwe’chi’eXen, a village site and cemetery for at least 3,500 years and thousands of ancestors of the Lummi Nation.

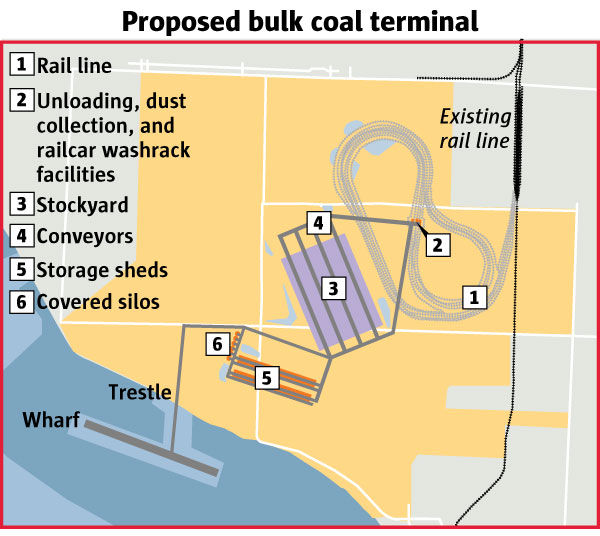

The Gateway terminal would move up to 48 million metric tons of coal a year — enough to cover 80 acres in five open stockpiles by the water, each 2,100 feet long and up to 70 feet high. As many as nine trains a day more than a mile and a half long would travel to and from the terminal, all the way from Montana and Wyoming. Every 18 hours, ships, many nearly three football fields long, would load up on coal at the 3,000-foot-long wharf.

Booming across the water in a tribal fishing boat toward Cherry Point, Lummi carver Jewell Praying Wolf James said he traces his lineage to some of the first sockeye fishers with reef net sites here.

To him, and to tribal cultural leader Al Scott Johnnie, the fishery means more than money. “There is a sense of place, a sense of belonging and a culture of the water, the air, the plants, the fish, and how you conduct your relationships,” Johnnie said.

continued below~

This painting in the new Lummi tribal center depicts a traditional Lummi village with cedar plank homes. The ancestral village at Cherry Point would have looked like this. (Alan Berner/The Seattle Times)

Community allies

The Gateway project has become a referendum on the dirtiest fossil fuel of all: coal.Burning coal creates pollution that harms human health and the environment. In addition to particulates, burning coal generates more carbon dioxide emissions than any other fuel, implicated as the number one source of human-caused climate change.

So while SSA Marine’s subsidiary, Pacific International Terminals, proposed its project way back in 1991, the issue didn’t blow up until the company revealed in 2011 that coal, not grain or potash, would be king at its terminal for the near future — just as the politics of coal and climate change detonated in the Northwest.

Thousands of people have turned out to oppose the Cherry Point coal port, and a second coal terminal proposed in Longview, Clark County. Even Coal Age News remarked in March 2011 on the “potentially defining regulatory battle to build the ports as legions of enraged enviro-zealots gird their hemp-laced loins at the thought of dirty American coal being sent to even dirtier Asian power plants across the blue sea.”

Community residents who once felt powerless to stop the project say they took heart when the tribes weighed in.

“They are protecting their own culture and their children’s children, but they are also protecting everyone else,” said Beth Brownfield, a Bellingham resident whose church has made common cause with the Lummi. “In our political system, you have no voice, it’s write a letter or go to a meeting, you are like a drop of water. But with their treaty and their sovereignty and their history, people are looking at that and saying, that will make a difference.”

Needed jobs

For SSA Marine, and backers of the project in the local community, the situation is profoundly frustrating.“There are a lot of people who don’t want things to change,” said Bob Watters, senior vice president of the company, which operates in 22 countries and is the largest privately owned terminal and cargo handling operator in the world. “But things constantly change. The best way to make that happen is to sit down and figure out how to make it easiest for everyone involved.”

Proposed coal shipping terminal at Cherry Point

The proposal by international shipping giant SSA Marine has hit a wall of resistance from tribes, especially the Lummi Nation.

Sources: Esri, Washington Department of Ecology

MARK NOWLIN and GARLAND POTTS / THE SEATTLE TIMES

But times have changed for the company, too.

“The pivot point, when all this happened, was when coal became the major commodity” for the project, said Jim Waldo, the attorney hired by SSA to help the company get the necessary permits. “It just shut down any dialogue.”

Watters agreed. “It’s the toughest thing I’ve ever worked on,” he said. Now even the economics of the project have soured, with export markets in the tank and coal prices in a 15-month slide. But Watters says SSA is looking long, and expects coal to recover, providing company profits and jobs at its wharf for years to come.

John Munson, 74, a retired union longshoreman for more than 41 years, lives near Cherry Point and backs the project, and the high wage industrial union jobs it would bring in a community that keeps losing them.

“We absolutely need it,” Munson said of the project. “People are so upset that their children have to leave the community to find a job where they can make a living.”

Relations with SSA, founded in Bellingham in 1949 and based in Seattle, deteriorated after the company in 2011 drilled test borings at the site without proper permits and disturbed a shell midden.

Watters said the drilling was a mistake and recently sent a letter from SSA’s lawyers to the tribe threatening to sue for defamation if the tribe publicly says otherwise, another measure of how toxic relations have become.

“They won’t even talk to us,” Watters said of the Lummi.

“This is displacement”

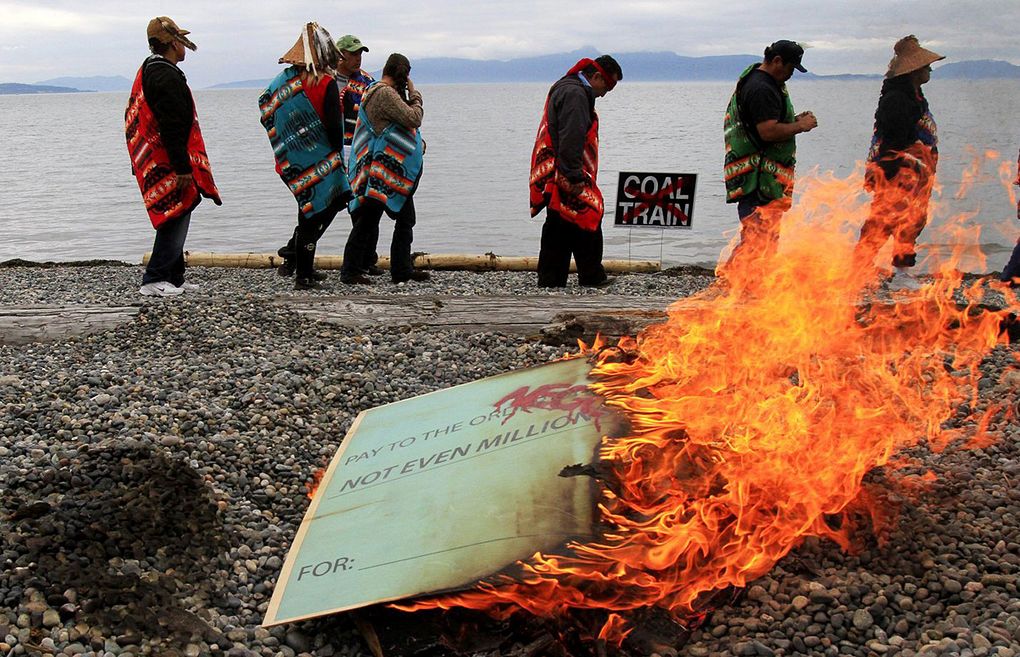

Meanwhile the Lummi and other tribes keep expanding the front of their fossil fuel fight.After the drilling fiasco, the Lummi ceremonially burned a check on the beach at Cherry Point, declaring their unalterable opposition to the project, and embarked on rallying opposition at every Indian reservation between their homeland and the coal fields of the Powder River Basin.

Tribes around the northwest have proclaimed their support for the Lummi’s treaty rights fight, and joined in opposition to Northwest fossil fuel transport projects.

Swinomish has sued the BNSF in federal court to block transit of oil trains through its lands. On Washington’s outer coast, the Quinault Indian Nation is opposing the construction of oil train terminals in southwest Washington, including Tesoro’s Vancouver project, which would be one of the largest oil-by-rail unloading facilities in North America.

We have to make a stand before this very destructive poison they want to introduce into our backyards.” - Brian Cladoosby, chairman of the Swinomish Indian Tribal CommunityThe exception is the Crow tribe in Montana, a part owner in the Gateway project. The tribe wants the money that mining the coal from its reservation lands would bring.

The Lummi’s treaty rights violation claims are the most developed, with hundreds of pages of objections now under review before the Corps. With the biggest native fishing fleet on the West Coast, the tribal fishermen filed objections that testify to their economic and cultural stake in these waters.

“This is displacement, no different from when they burned our villages,” one wrote. “We look like ants compared to these huge ships,” wrote another. “Our world is getting smaller and smaller,” wrote another fisherman, and “We can’t lose any more spots,” said another. “No means no. How many times do we have to say no?”

More than 150 boxes of unearthed archaeology from the village site curated at Western Washington University testify to the tribe’s deep history in these waters. A stone anchor weight kept at the Lummi’s tribal center dates back more than 3,000 years.

The corps could make a decision at any time as to whether the project, planned for full operation by 2019, poses more than a minor disruption to the tribe’s treaty protected fishing rights, and therefore must be denied. Watters argues the best track would be to let the ongoing environmental reviews play out, and resume negotiations.

This is displacement, no different from when they burned our villages.” - Tribal fishermanSSA in December submitted its final development proposal to the Corps with a reconfigured footprint to reduce destruction of wetlands by about half. The proposal also includes a range of measures SSA contends will lessen impacts on tribal fishing and make the waters safer than today.

For Bill James, hereditary chief at Lummi, this fight isn’t over only crab and salmon fishing grounds, but something bigger, schelangen, their people’s way of life. Mitigation here or there, of this or that impact, doesn’t capture what would be lost if the last of this cove was developed for industry, James said. And he remembers being personally charged by his elders to protect the spirits of the tribe’s first ancestors whose burials are at Cherry Point.

He recently walked the beach at the proposed project site, picking his way along the cobble with a walking staff, as a loon called, and gulls massed over herring in the sun- silvered water. “Here comes Loon to listen,” James said. “And there’s Herring.

“It’s always wonderful to be here.”

No comments:

Post a Comment